Sam Denny spent nearly his entire life on the banks of the St. Lawrence River. It provided his income, inspired his art, and would be the key to having his name and work remembered around Clayton, New York (and beyond) more than a half century after his death.

When you step into the Thousand Islands Museum, it doesn't take long before you encounter the work of Sam Denny. Famed for his hand-carved wooden duck decoys, an entire room is dedicated to his ducks and paintings, as well as the photos that tell the story of his life.

Like his father before him, Sam worked as a river guide. A skilled oarsman and angler, he led expeditions for scores of businessmen and vacationers that made their way to northern New York to experience the bounty of one of the most picturesque waterways in the country. Bass, Northern Pike and Muskellunge were plentiful in the St. Lawrence and scenes like the one below were common after a day on the water.

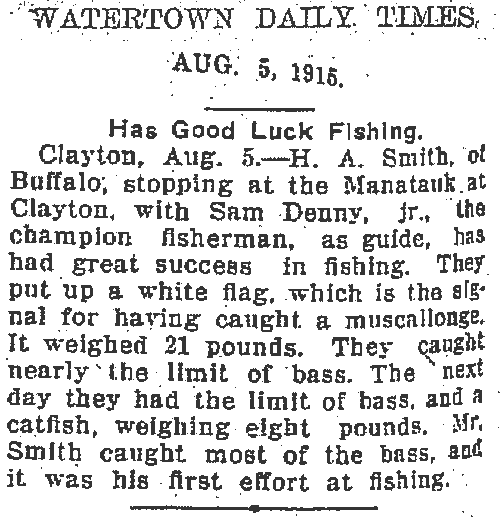

Sam's notoriety quickly spread beyond the small village of Clayton. Details of his guide trips were often highlighted in local papers as customers from around the state and country had their proud moments documented in black and white for all to see. The two newspaper articles below illustrate some of Sam's time on the water. A skiff race winner in June of 1900 and guiding a first-time fisherman during the summer of 1915 to the catch of his life!

1915 Fishing Expedition

Skiff Race Winner on June 1, 1900

Sam Denny, far right leaning on tree, with the day's catch in Clayton, New York. Photo Credit: Les Corbin

For as noted as Sam Denny was as a river guide, he is best remembered as a masterful carver of wild duck decoys. He began to carve decoys around 1900 and would continue for the next 50 years. His ability to transform a block of cedar into a work of art, both functional and beautiful, earned him a reputation as one of the most skilled and in-demand carvers of the day. Sam's decoys have remained a topic of discussion decades after his death as collectors debate the finer points of his methods and share tips on how to properly identify his work.

Sam Denny received national recognication when he was postumhously profiled in the 1968 Annual Decoy Collector's Guide. In a five page article by Harold B. Evans, Sr., Sam's methods and attention to detail were noted: "He experimented a great deal with paint after securing a book on paint chemistry by mail. He used banana oil and colodion to produce a flat finish. To prevent "icing up" and shining on decoys used in January shooting, he applied a coating of beeswax dissolved in turpentine. And because cedar did not always hold paint well, Sam used a special primer of his own concoction." Always a perfectionist, the process of painting would take a week for each decoy produced.

Evans goes on to say "In the early 1900's, Denny charged 75 cents each for his birds, a high price in those days. By the fourties his price had gone to $5.00 each for blackduck, a bit less for other species. Even at this price he could not keep up with demand and was always sold out long before the duck season opened."

It's estimated that Sam carved around 150 decoys a year, with his peak production year topping out around 400. Theodore Denny shared a story for a 1968 Watertown Daily Times feature story that "his father once worked overtime to produce two barrels of pintail decoys for Abercrombie and Fitch in New York City. He shipped them and immediately received an order for 1,000 more. This, Theodore recalls, floored his father and he ripped up the order and threw it away in disgust."

As the years go by, his decoys are harder to find, but still very much in demand and selling for hundreds of dollars at auction.

When he was not guiding on the river, carving decoys or harvesting ice, you were quite likely to find Sam painting outdoor scenes or playing the fiddle. Just as he was a self-taught whittler, he used his natural talents to become an accomplished painter and musician. The Daily Times article goes on to say "Sam taught himself to play violin, probably starting out on a homemade fiddle his sons remember seeing around the house long after he aquired factory-made instruments. Not content to play just the simple tunes he picked up by ear, Sam learned to read music and became an accomplished violinist."

Painting and playing music brought joy to his life. Clayton Historian Norm Wagner once told me how Sam's neighbors would clear a room in their house for impromtu dance gatherings with Sam providing the evening's music in exchange for a freshly baked pie.

Sam studied paintings of the masters and would practice his skills by recreating the their work until he could perfect certain techniques and effects to apply to his originals. He painted what he knew best, scenes of nature and life around Clayton as seen in this depiction of the cabin on French Creek.

Sam Denny grew up in a small immediate family, just himself and his younger sister Lillie. That certainly didn't influence the size of his own family, which was big even by the standards of the day. It has been reported that Sam and Salina had 15 children, although I have only been able to document 13 of them at this point. The ninth of those children was my grandmother, Geneva.

Tracing Sam's early life starts with a mystery right off the bat, the year of his birth. America's record keeping in the 1800s was spotty at best and varied widely by state, county and town. Sam's date of birth has been reported as September 25, 1874 -- you'll see it in newspaper articles and even on his gravestone, but there is nothing concrete that I have seen to support 1874. There is, however, more convincing evidence that Sam was born the year before, in 1873.

A genealogist's goal (dream) is to have a primary source to support each fact/date in a person's life. "Primary" means a record that was created at or around the time the event occurred. The primary source in this case would be a birth record from the town of Clayton or a baptism entry in the parish register at St. Mary's Church -- neither of which exist. In the 1870s, townships were not yet required by the State of New York to keep records and while there are church records from that era, it is believed that Sam's parents didn't marry until 1875 (again, no primary source) making it unlikely that the baptism of a child with unwed parents would be recorded by the church. With these facts in mind, we turn to secondary sources and logic to determine Sam's birth date.

St. Mary's Church has a record of Sam's younger sister Lillian as being baptised on April 21, 1875 and a birth date of April 15. If we were to believe that Sam was born on September 25, 1874, that was only 6 months and 21 days before Lillian's birth -- obviously not very likely. Our second clue comes from the 1875 New York census taken in June of that year. It lists Lilly as being one month old and Sam as 1 year, 10 months. Census records often contain errors and there certainly was no proof of age required by the enumerator, but logic suggests that Sam would have been born in 1873. The third clue are two documents signed by Sam Denny himself -- a 1918 World War I draft registration card listing "Sept 25 1873" as his date of birth (Note the varient spelling of Denney with an extra e) and his identification card issued by the U.S. Coast Guard. Again, this assumption is largely based on secondary sources, but 1873 makes much more sense that 1874.

While Sam and his sister were born in Clayton, census records tell us that by June 1880 they had relocated to Oconto, Wisconsin. The reason for this move to the midwest was most likely to the desire for Sam's mother, Salina, to be close to her oldest child, from her first marriage, Jennie Benway. (Note: Salina had been married to Ziba Benway, who died in 1865 after his Civil War service). Jennie married Charles Collier and had been living in Wisconsin since at least 1874. At the time Sam's parents moved to Oconto, Jennie had three small children and it's quite possible that Salina had never met any of her young grandchildren.

Tracking exactly how much time they spent in Wisconsin before returning to New York is a bit of a mystery. The next census was taken in 1890, but nearly all of those records were destroyed in a 1921 fire leaving a large gap in the history of that time period. The New York State census of 1892 is also of little help as the records from Jefferson County have been lost as well.

In the winter of 1896, Samuel Joseph Denny, Jr., 22, married fellow Clayton native Salina Mary Amo, 17. Both were first generation Americans, both of French Canadian descent. The couple had likely known each other since their early school days and by the time they were married on Monday, February 17, 1896, Salina was pregnant with their first child, Norbert.

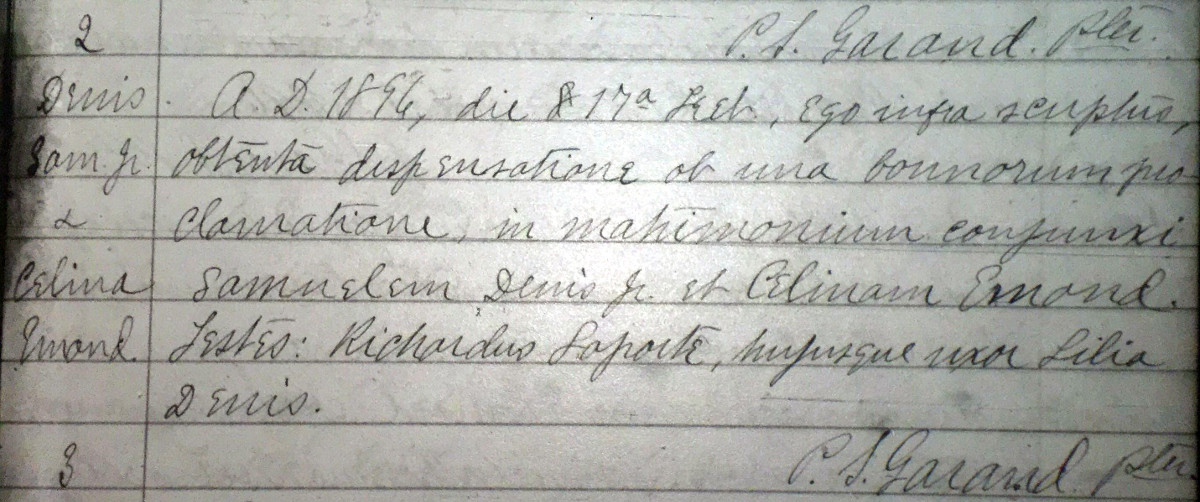

Marriage record of Sam Denis, Jr. and Celina Emond, St. Mary's Church, Clayton, New York

The marriage record shows the church's attempt to preserve the French heritage of so many of Clayton's residents. Instances like spelling "Denny" as "Denis" and using the original "Emond" instead of the Americanized "Amo" can be seen throughout the records of that era at St. Mary's.

Sam and Salina had more than a dozen children over a span of 24 years. Here are some of their baptism records from St. Mary's Church in Clayton:

Sam's wife Salina fell ill in the fall of 1931 and passed away on the 5th of May in 1932 at the A. Barton Hepburn Hospital in Ogdensburg. At the time, Sam still had a large family at home -- his 17 year old daughter Geneva, and the four youngest boys ranging in age from 12 to 15.

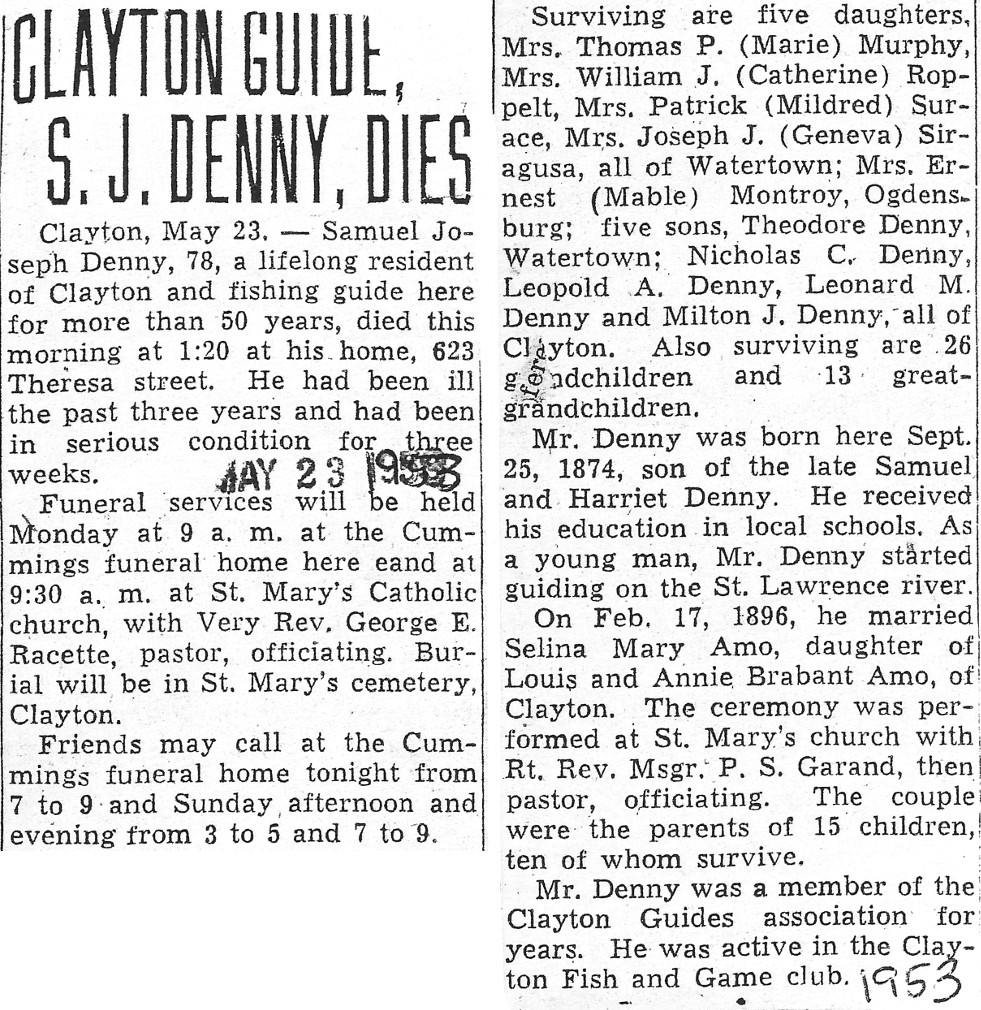

Sam lived for another 21 years and never remarried. He kept busy leading fishing expeditions, carving countless decoys and enjoying his two favorite hobbies, painting and music. At 78 years old, Sam passed on May 23, 1953.

Obituary of Sam Denny from the Watertown Daily Times, May 23, 1953

I never had the chance to meet Sam Denny, as he died more than a dozen years before my birth, but I carry his name as my middle name, as my father did before me. -JSS