Lester C. Angell, 1862

The war between the states had begun more than a year earlier with the rebel assault on Fort Sumter (April 1861) and quickly grew into the greatest conflict that the young nation had seen since the Revolution.

In the months that followed, President Lincoln called upon congress to authorize hundreds of thousands more men to join the fight to preserve the Union.

Recruitment posters and newspaper want ads for men were commonplace across the counties of New York state. They offered bounties, good pay and good rations. In the case of the artillery, even "no trenches to dig" or "heavy loads or knapsacks" to carry. (Below, August 6, 1862 ad from the New York Reformer, Watertown. Click to view full ad.)

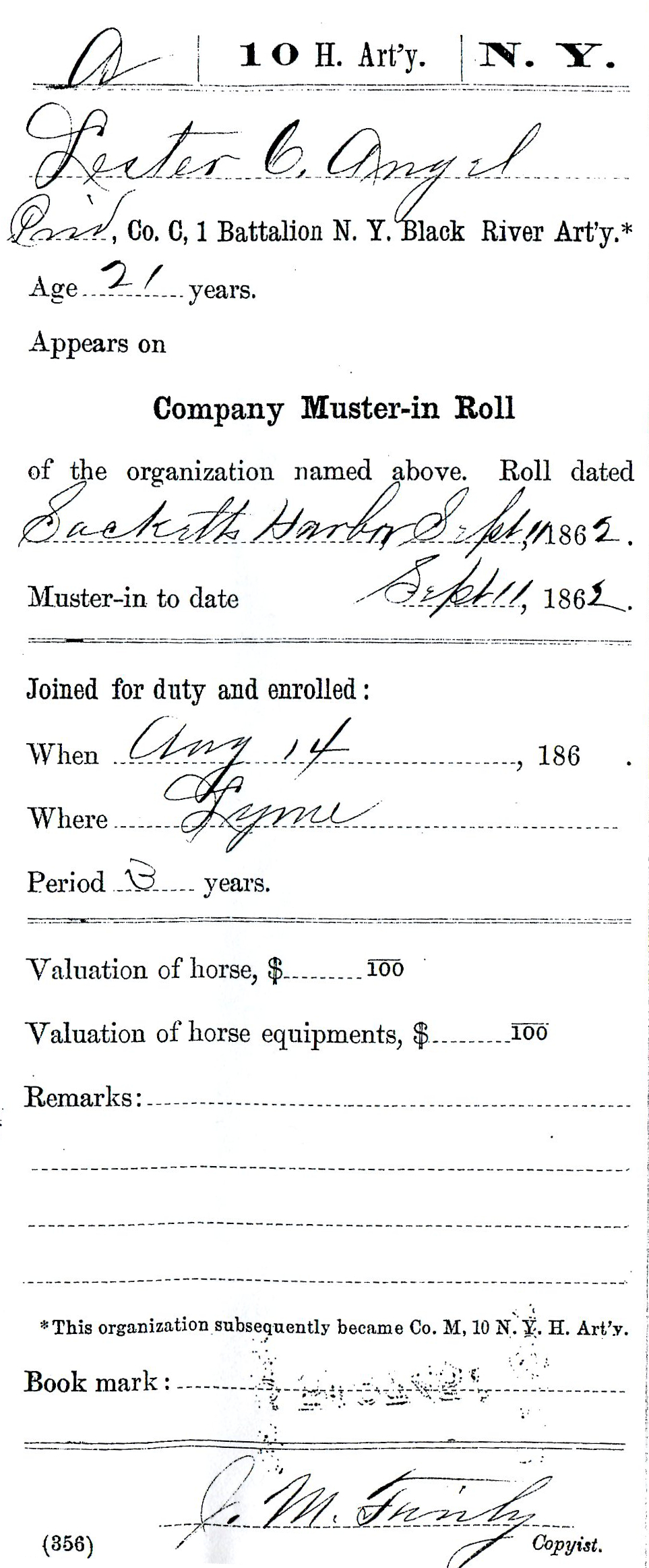

Lester Angell worked as a farmer in Cape Vincent, New York and married Ann Eliza Baird in the fall of 1861. They had given birth to their first child, Anna Lettie Angell, in June 1862. Leaving his wife and newborn child with his extended family, Lester answered the call of duty and enlisted for a period of three years in the Union Army on August 14, 1862 -- just two week before his 22nd birthday.

Recruitment Advertisement from Watertown newspaper

On September 11, 1862 he mustered-in at Sackets Harbor and began his training at the site made so locally famous by a War of 1812 battle. Private Lester C. Angell was now a member of Company C, 1 Battalion, New York Black River Artillery.

Lester C. Angell, Muster Card, 1862

The new recruits were organized, quartered, and hastily trained at Sackets Harbor as they awaited orders. One week after being mustered in, they received word from New York Governor Edwin Morgan that they were to proceed to New York City for equipment. On Thursday, September 18th, 1862, the first and second battalions, including Lester's Company C (later renamed to Company M), marched from Sackets Harbor to the railroad junction of the foot of Arsenal Street in the village of Watertown.

Captain E.B. Webb published remembrances of the day in his 1887 book History of the 10th Regiment: "This march was accomplished in good time through a broiling September sun, the men, in heavy marching order, carrying their haversacks, knapsacks and canteens, together with much et ceteras as the civilian soldier deems necessary to his comfort." Webb further recalls the many friends and family members of the men that greeted them along their route, and that "the ladies of Watertown and vicinity, anticipating their arrival, hunger and weariness, had prepared at the hotel then kept by S.P. Huffstater at the Junction, an ample repast of sandwiches, coffee, etc., to which the tired and hungry soldiers did ample justice." That afternoon, 1200 men boarded 24 New York Central Railroad coaches "amid the cheers of the soldiers and the tears of the friends they left behind" and set out to war.

On September 19, the men arrived at Park Barracks in New York City. They were allowed to visit any portion of the city, a novelty for many, and requisitions were made for camp equipment including tents, blankets and cooking utensils. Their stay in New York was brief -- within 48 hours they boarded a boat and sailed down the river to Camden, New Jersey. From there, they proceeded by rail to Philadelphia, Baltimore, and ultimately Washington, D.C.

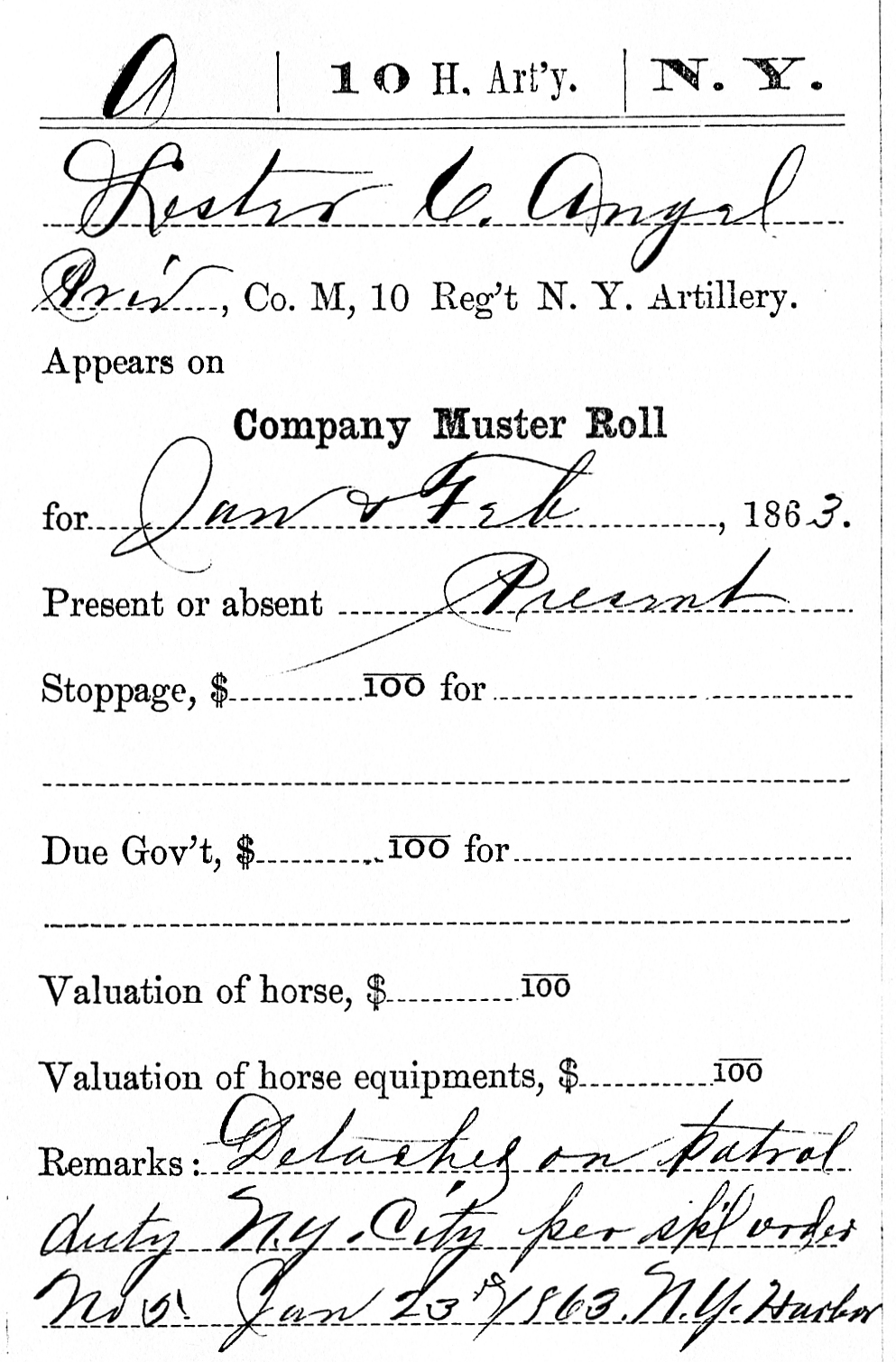

The regiment's first assignment of the war was defence of the nation's Capitol. Southeast of the city, at Fort Baker, they set up camp and were drilled in light and heavy artillery tactics. During this time in the fall of 1862, Captain Webb recalls the confusion and disagreement over the organization of the troops. After much discussion and politicking of Governors, Generals and various officials, the regiment was reorganized by the end of the year. Lester Angell's original Company C of the 1st Battalion was now known as Company M, 4th Battalion.

The 10th Regiment was highly regarded for its duty of defending Washington and being "the only barrier between the rebel forces and the National capitol, in case the enemy should force the Federal lines, and make a raid into Maryland," writes Webb. While they would remain in this garrison service until March 1864, some of the men, including Lester, were detached to similar duties around New York Harbor. The following muster card shows January 23, 1863 as Lester's date of detachment to New York City, where he would serve for the next six months.

Detached service to New York Harbor

With battles raging in Virginia in May and June of 1863, the detachment was ordered to return to Washington, D.C. to once again help protect the Capitol and also to guard deserters as indicated on the muster card below. 80 miles to the north, the pivotal battle of Gettysburg takes place July 1-3.

Detached to Washington, D.C.

Letters written by soldiers and sent to newspapers back home provide a further glimpse into their lives during the war. The following is an excerpt of a letter from a Company A soldier (only identified as "NIX") describing their impromptu 4th of July celebration at Fort Baker. Lester's company was very likely part of this celebration. You can find more clippings here, courtesy of the New York State Military Museum.

Head Quarters 10th Reg. N. Y. Art'y

FORT BAKER, D. C.

July 7, 1863.

ED. UNION--Thinking perhaps that the friends of this regiment would be pleased to learn how we celebrated the Anniversary of our Nation's Independence, I propose to favor you with a "certified report." I must confine myself more particularly to the doings of Co. A. I will say, in the outset, that no arrangements were premeditated, but our celebration was gotten up on short notice; and though not very extensive, it served greatly to drive away the sadder feelings of loneliness and home-sick- ness which were called forth by the memories of other and happier "fourth of Julys" spent by the members of this company in connection with the "dear ones at home," from whom we are now so unhapily separated. [...]

Early in the morning the men commenced putting up an awning, tables and seats, upon our parade ground, in front of their quarters. At about 10 o'clock all was completed and the table commenced to be laden with the good things. At each end of the table was a pole from which floated the stars and stripes, while across one end attached to a board was the (to the Rebs.) ominous words "The Union forever," in large letters cut from green moss. The tables were soon spread with as much taste and variety as one often sees even where greater facilities are at hand. The bright tin cups and plates presented a strong contrast to what one is used to see upon such occasions at home, but I dare say the edibles were equal in variety, quality and quantity to what is often seen at celebrations making loftier pretensions than ours. Such a host of good things could not often be found at an old fashioned Jeff. Co. Fair or General Training. Our Regimental Band, under the leadership of the redoubtable Milt. Reed, was present and furnished some lively music. "Hail Columbia" was the signal for calling out the company, which promptly appeared, bayonets fixed. They were marched by platoons to each side of the line of tables, stacked arms and broke ranks, to form again and charge upon the edibles spread before them. -NIX

Published letter from Company A soldier "NIX", 1863

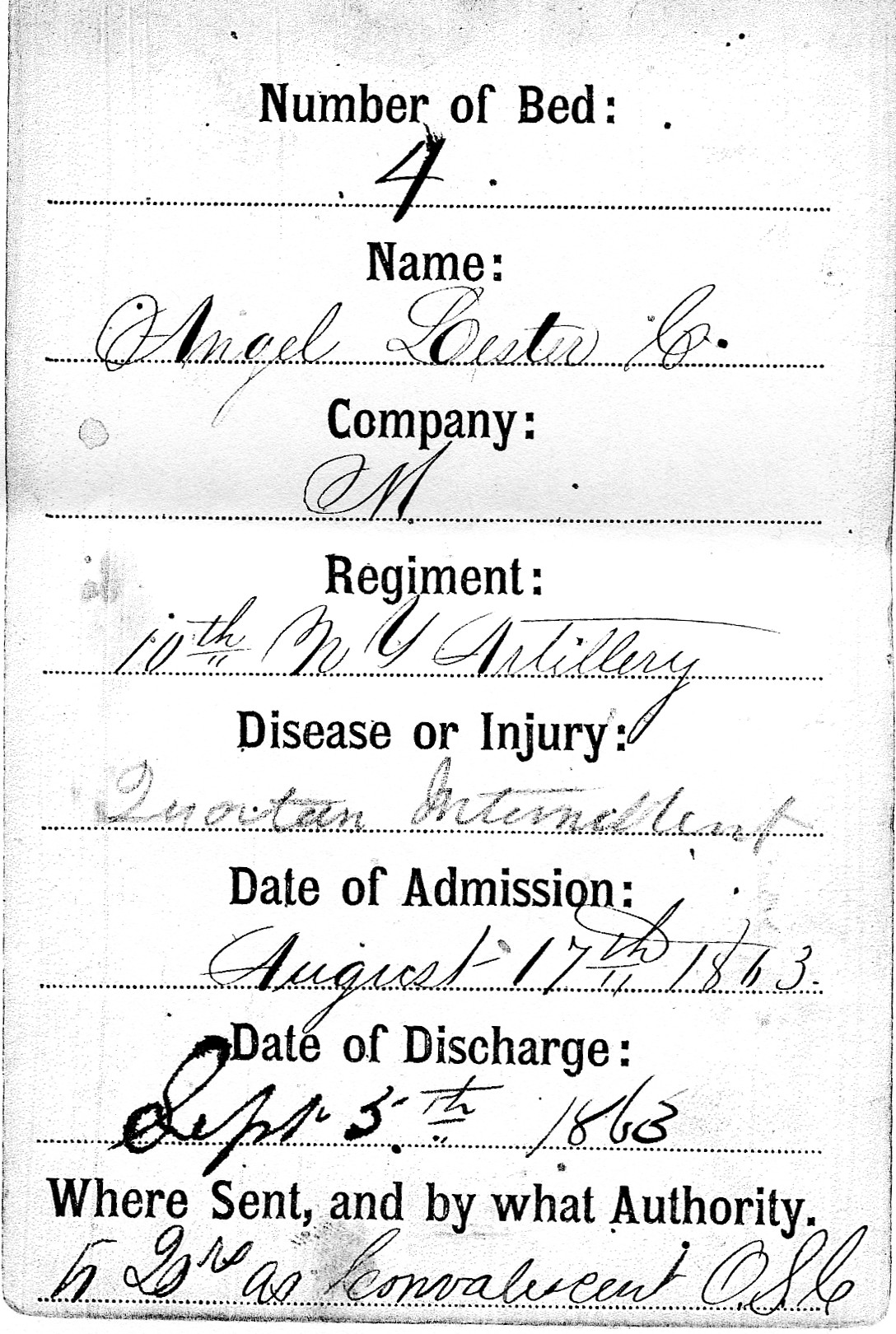

After less than a year of service, Lester Angell was promoted to the rank of Corporal on July 31, 1863. In mid August, he fell ill and was admitted to the regimental hospital with intermittent malaria. With the unsanitary battlefield and camp conditions of the time, disease was quite common throughout the war. It has been estimated that for every three soldiers that died in battle, five more died from disease. This admission to the hospital was the beginning of perhaps the most challenging aspect of Lester's service.

NOTE: While malaria is most often associated with more tropical climates, it was a common ailment in the American Civil War. National Geographic reports that "In the late 1800s, malaria was so bad in Washington, D.C., that one prominent physician lobbied - unsuccessfully - to erect a gigantic wire screen around the city. A million Union Army casualties in the U.S. Civil War are attributed to malaria."

At regimental hospital, Fort Baker, D.C.

After three weeks in the regimental hospital, Lester was sent to another convalescent facility, most likely near Arlington, Virginia. "Sick in hospital" is the most amount of detail that exists on muster cards for the next few months. On February 2, 1864, after nearly six months of illness, Corporal Angell was issued a sick furlough and allowed to return to his home in upstate New York for 40 or 60 days (there are conflicting reports of the furlough's length).

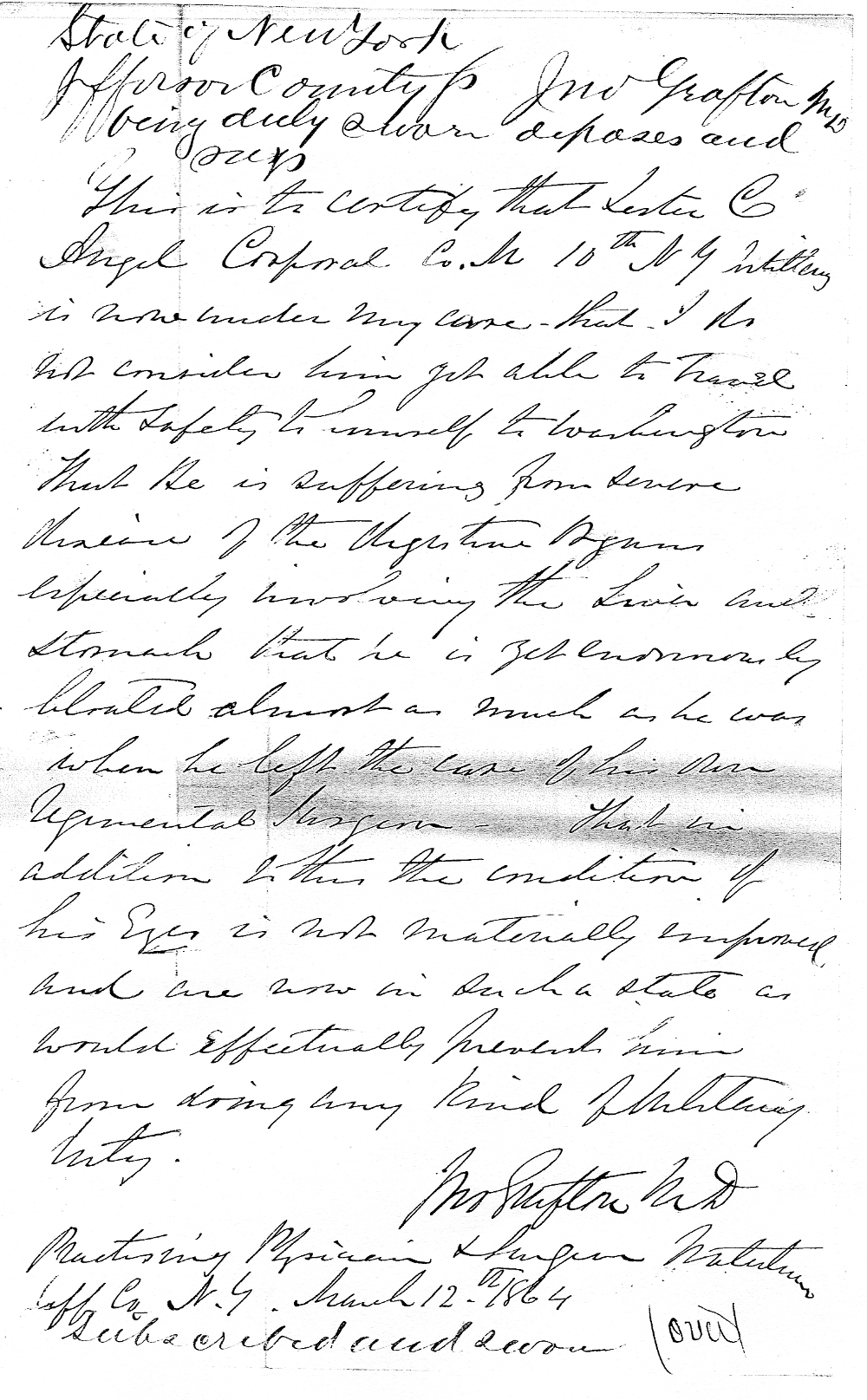

In February 1864, Lester Angell returned to Cape Vincent and was reunited with his wife and 20 month old daughter as he recuperated from the lingering effects of malaria. On March 12, as his furlough was coming to and end, he was examined by Dr. John Grafton, a prominent surgeon in Watertown. In the affidavit below, the doctor states:

"I do not consider him yet able to travel with safety by himself to Washington. That he is suffering from severe disease of the digestive [system?] especially hindering the liver and stomach. [...] [He is in] such a state as would effectively prevent him from doing any kind of artillery duty."

This statement ostensibly extended Lester's furlough...or so he thought.

Letter from Dr. Grafton

After forwarding the surgeon's letter to his command, Lester remained in Jefferson County for the next five months. During this time the 10th Artillery continued their garrison duties at Fort Baker until being pressed into active service at the Battle of Cold Harbor in early June 1864.

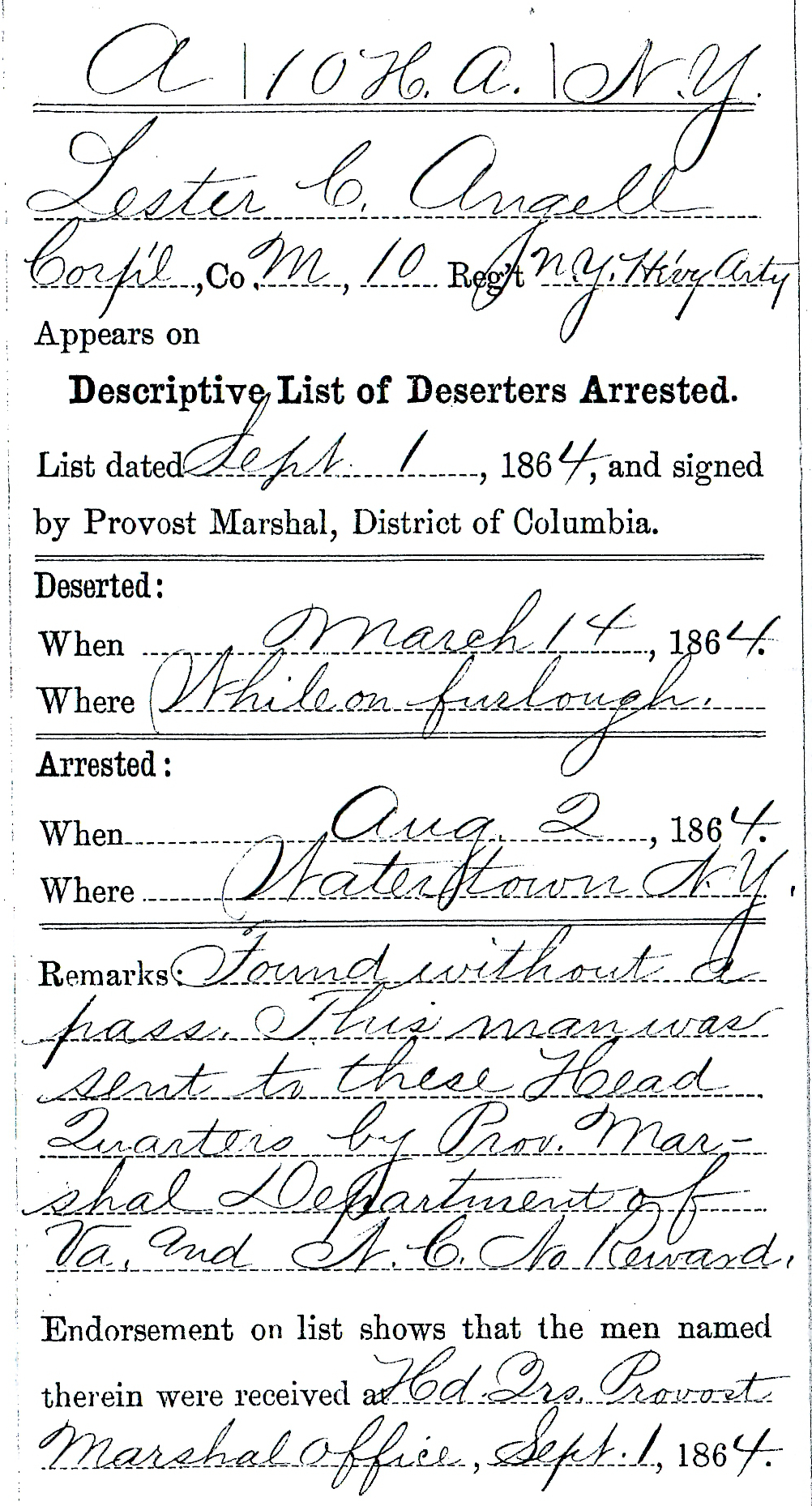

On the morning of August 2, Lester set out to rejoin Company M. His brother-in-law Christopher Baird took him by carriage to the station of the Watertown & Rome Railroad, where Lester boarded the train and traveled 25 miles to the office of the Provost Marshal in Watertown to obtain the required pass that would allow him to return to duty in Virginia. Instead of receiving his pass, he was told that his furlough had expired, and he was arrested as a deserter. (View Christopher Baird's statement)

Lester Angell's 1864 Arrest

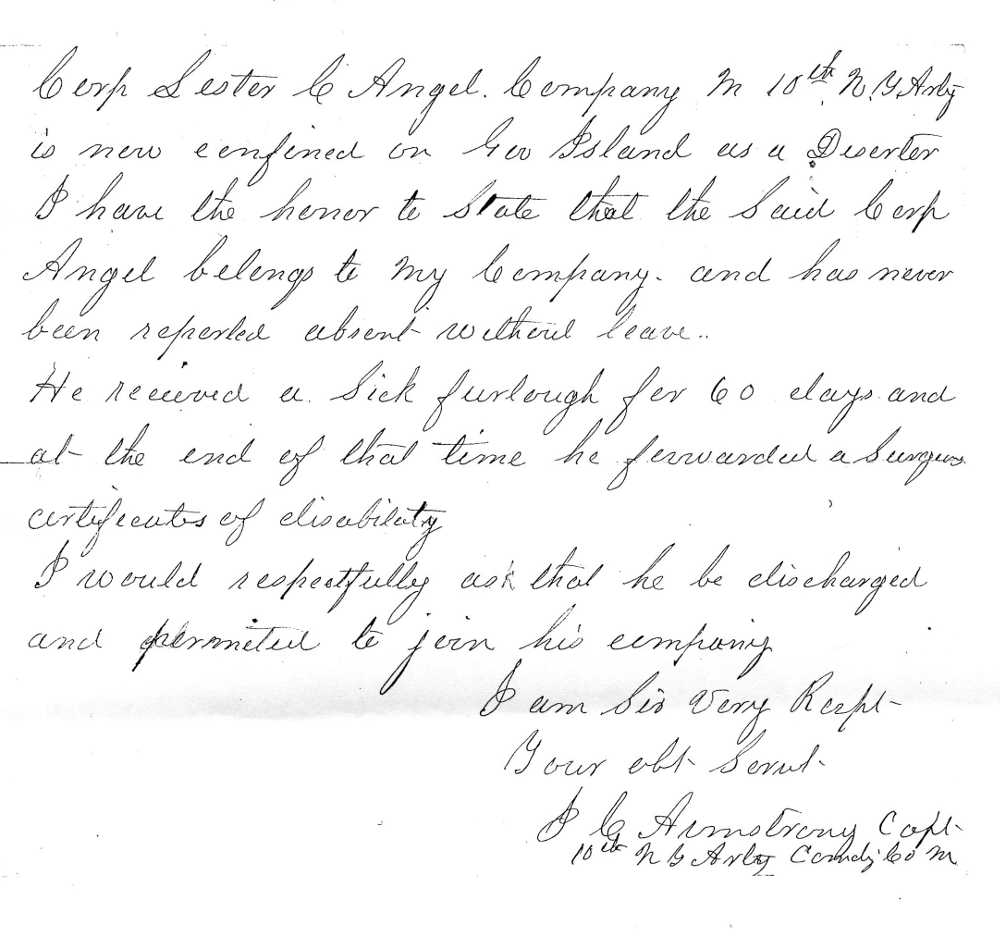

Today, a situation like this could probably be solved with a few phone calls and a couple e-mails. The exchange of information in 1864 was not as swift, and it took the next two months to sort out the affair. Lester provided documents from the surgeon as well as sworn statements from Christopher Baird, Morgan Klock, and his father David W. Angell detailing his illness and intent to rejoin his company. At some point, Lester was transferred to the Washington Street Prison in Alexandria, Virginia. His commanding officer, Captain Armstrong, also came to his defense and by November 1864, Corporal Lester C. Angell was back on duty with Company M.

Letter from Lester Angell's commanding officer, Captain J. Armstrong

After more than a year of illness, arrest, brief imprisonment and acquittal, Lester is finally able to rejoin his brothers in arms. In mid September 1864, he was transferred to Fort Whipple, Virginia, where the 10th was now stationed. The men were ordered to join the Army of the Shenandoah at Harper's Ferry on September 23. From there, they served guard on General Sheridan's supplies and in October, fought to hold their position at Cedar Creek against Confederate General Early.

Late in the year the regiment was ordered back to the army of the Potomac, and on December 31, 1864, they made camp at Bermuda Hundred, just south of Richmond. There they were attached to the Provisional Brigade commanded by General Edward W. Ferrero during the ongoing Seige of Petersburg. As the 10th prepared to spend the winter in their position, back home on December 17, Lester's second child, Lillian, was born.

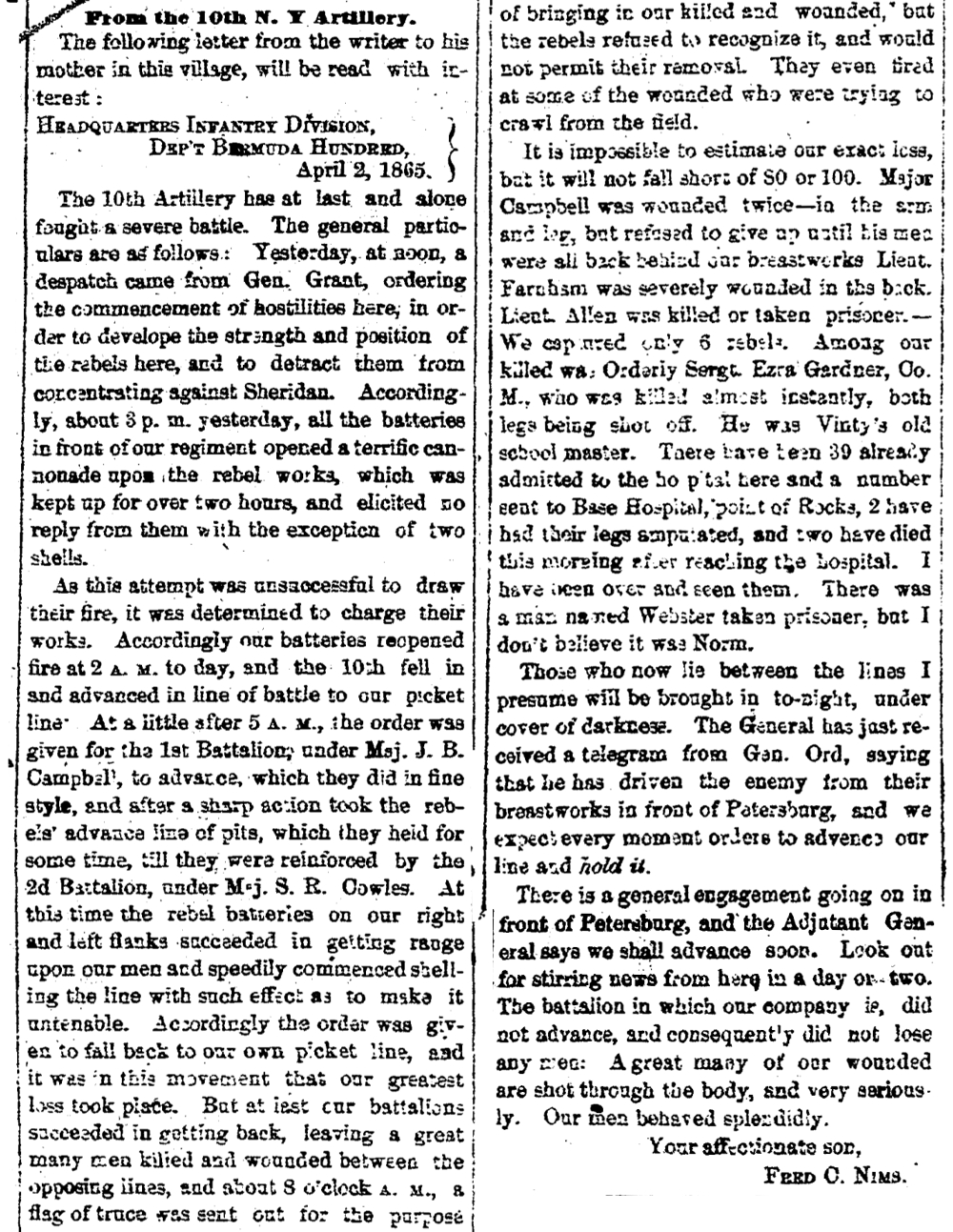

The final, and perhaps most fierce, battlefield actions of the 10th Regiment came on April 2 and 3, 1865. General Grant telegrammed that it was thought the enemy was moving their troops in an effort to concentrate on General Sheridan's position. The 10th was ordered to fire upon the enemy's line and ultimately advance on them. After a ferocious fight that resulted in dozens of casualties, including their Major J.B. Campbell, they were successful in their efforts. An account of the action from one of the men:

April 8, 1865 article from the New York Reformer, Watertown

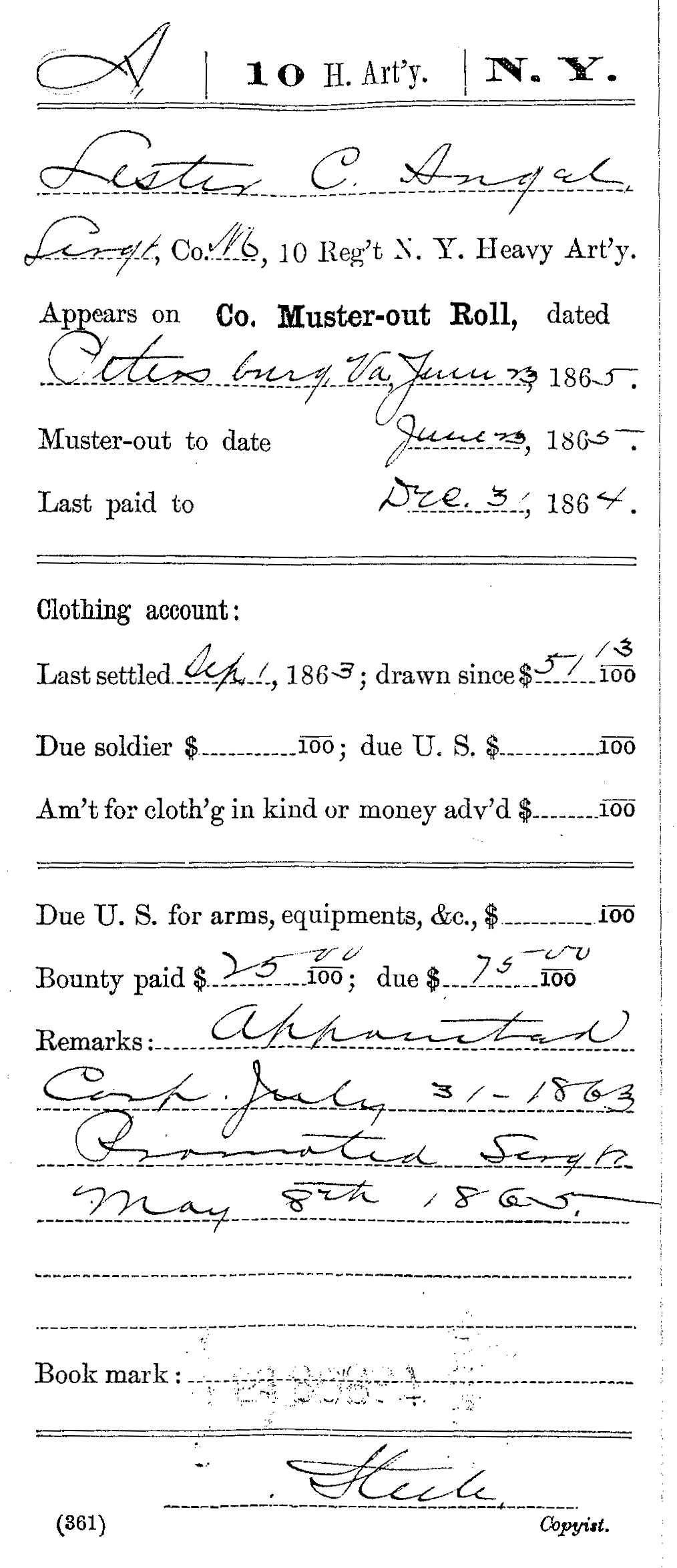

The cities of Petersburg and Richmond were taken back by the Union on April 3, just days before President Lincoln's assassination. A month later, as the war is winding down, Lester Angell is promoted to Sergeant on May 8.

On June 23, 1865, the final Confederate General, Stand Watie, surrenders in Oklahoma, which effectively ends the war. The troops of Company M muster out of Petersburg on that same day and begin their journey home.

Mustering out at Petersburg, 1865

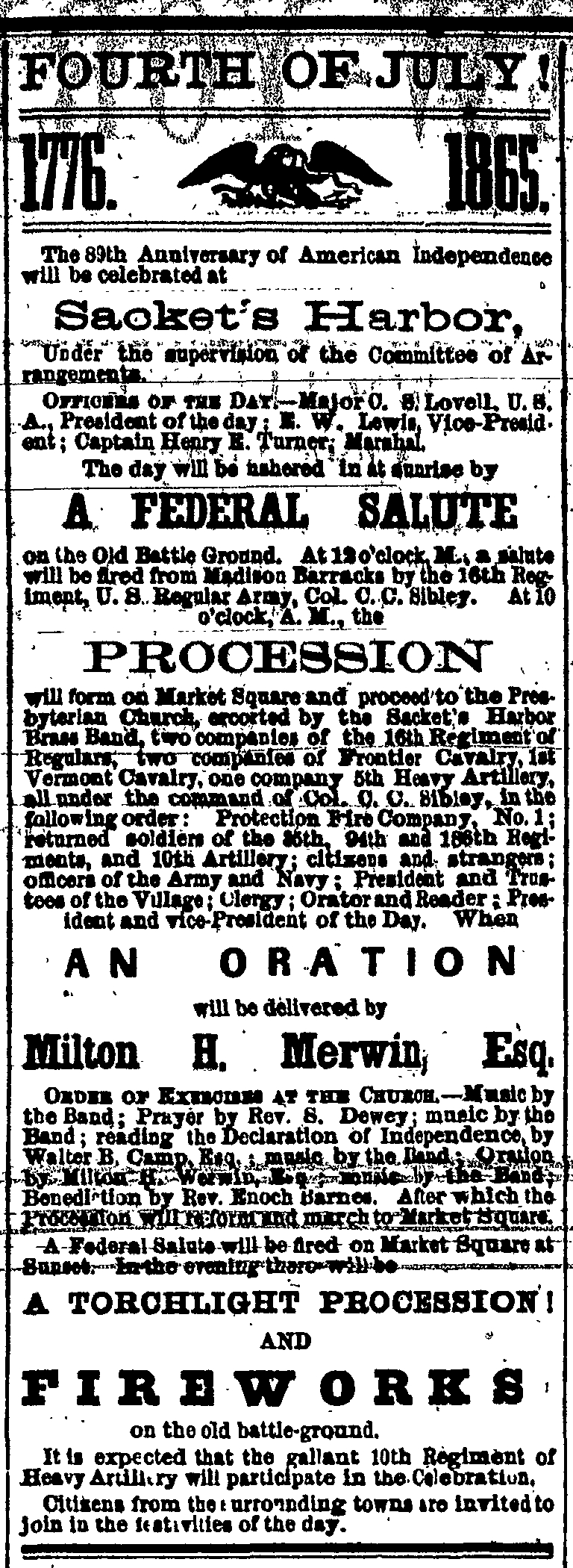

As the men returned home and the war was won, celebration and recognition of the those who served was evident throughout the area. One such event was planned for the 4th of July at Sackets Harbor, the place where it all started for the 10th Artillery three years earlier.

Announcement of July 4th, 1865 Festivities, New York Reformer, Watertown

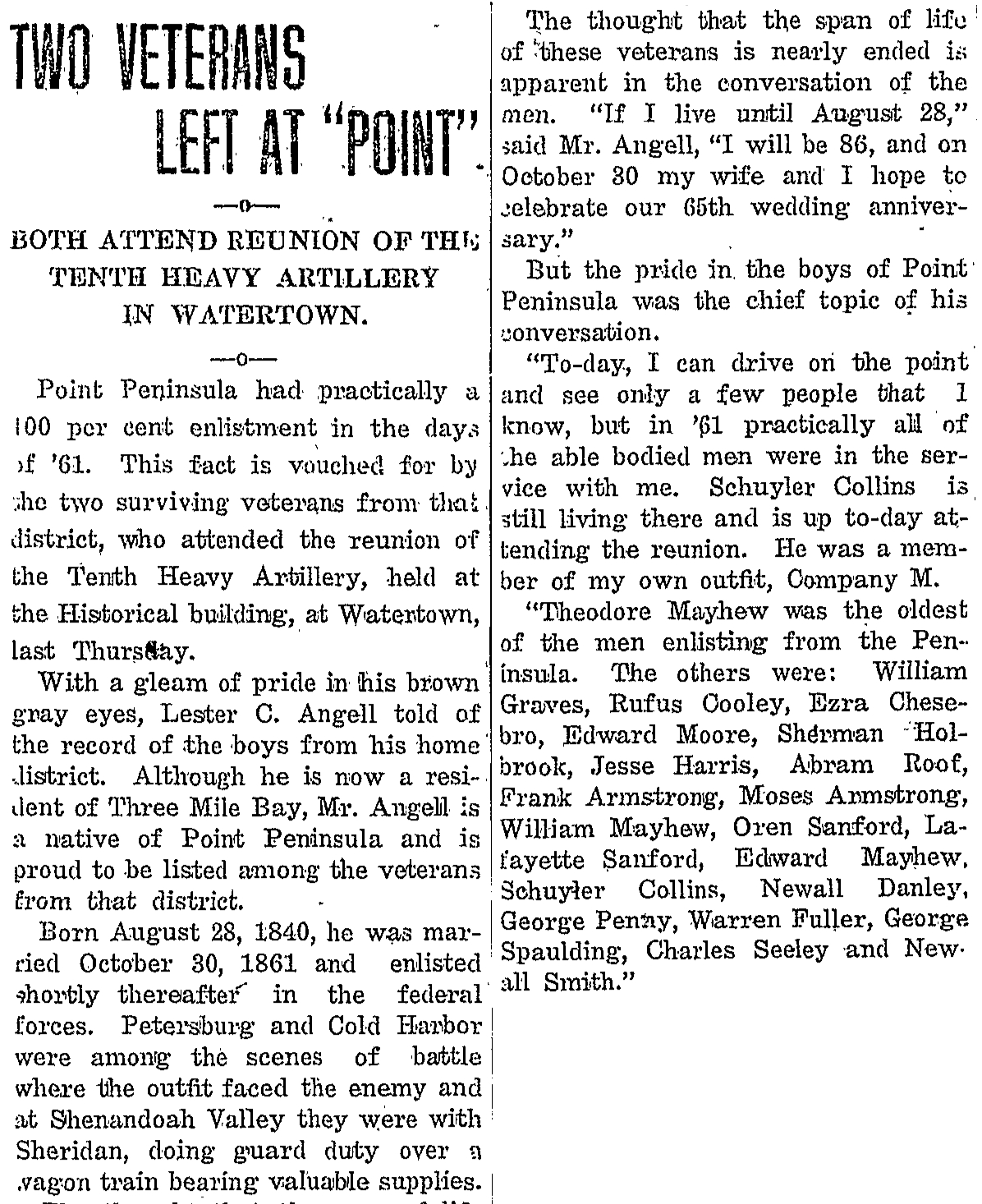

The men of the 10th Artillery held reunions over the years. Here is a newspaper account from the Cape Vincent Eagle with Lester's thoughts more than six decades after the end of the war:

July 29, 1926 article from the Cape Vincent Eagle

Source Notes: This account of Lester Angell's Civil War service was constructed using his military records from the National Archives, "History of the 10th Regiment" by E.B. Webb, newspaper accounts, information from the New York State Military Museum, and Census records.